The Plight of the Starving Artist – the CLASSICS Act may provide some relief.

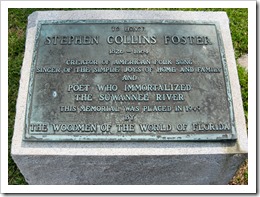

The plight of the “starving artist” is timeless and history is replete with stories of songwriters and artist being exploited for their intellectual contributi ons. In the mid 1800’s, when Stephen Foster wrote The Suwannee River, Oh! Susanna, Camptown Races, Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair, and Old Kentucky Home, the 1790 Copyright Act only protected “maps, charts and books” and thus did not extend to musical compositions. The only way Foster could conceive of earning an income from his craft was to sell his sheet music to traveling troubadours and minstrel shows, such as “Christy’s,” that traveled the country. The strategy worked in terms of getting his music exposure, but without adequate protective remedies, it created an environment where unscrupulous and dishonest publishers “bootlegged” his work and sold copies for their own profit. While most of the country knew Foster’s work (even today) because of this exploitation, he died a pauper in 1864 with less than a dollar to his name. So much for the post-Napster argument that illegally downloading and streaming music actually makes money for its creator by giving it wider exposure!

ons. In the mid 1800’s, when Stephen Foster wrote The Suwannee River, Oh! Susanna, Camptown Races, Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair, and Old Kentucky Home, the 1790 Copyright Act only protected “maps, charts and books” and thus did not extend to musical compositions. The only way Foster could conceive of earning an income from his craft was to sell his sheet music to traveling troubadours and minstrel shows, such as “Christy’s,” that traveled the country. The strategy worked in terms of getting his music exposure, but without adequate protective remedies, it created an environment where unscrupulous and dishonest publishers “bootlegged” his work and sold copies for their own profit. While most of the country knew Foster’s work (even today) because of this exploitation, he died a pauper in 1864 with less than a dollar to his name. So much for the post-Napster argument that illegally downloading and streaming music actually makes money for its creator by giving it wider exposure!

About 10 years following Stephen Foster’s death, mechanical sound recording technology was developed allowing reproductions of musical performances and thus began a revolution. Just over 50 years following that, transmission of sound waves via broadcast technology was invented and perfected, giving us the “music industry” as we knew it for over a hundred years. Had Foster lived another 20 years or so, he may have made millions of dollars as a result of his creations.

As a result of these n ewfangled and emerging technologies, and at least in partial deference to Stephen Foster’s unfortunate demise, Congress finally passed the 1909 Copyright Act which provided copyright protection for musical compositions, giving them an initial term of 28 years with one 28-year renewal period for the purpose of “prevent[ing] the formation of oppressive monopolies” which might limit those rights. See, H.R. Rep. No. 2222, 60th Cong., 2nd Sess., p. 7. Now, these newly protected musical compositions could be performed and embodied in sound recordings (although sound recordings were still not protected by federal law at this time), which could themselves be performed in broadcasts over the radio waves. It was an exciting time in the music business, which saw the rise of music publishers, record labels, radio stations, Harry Fox and all three performance rights organizations, ASCAP, SESAC and BMI, in that order.

ewfangled and emerging technologies, and at least in partial deference to Stephen Foster’s unfortunate demise, Congress finally passed the 1909 Copyright Act which provided copyright protection for musical compositions, giving them an initial term of 28 years with one 28-year renewal period for the purpose of “prevent[ing] the formation of oppressive monopolies” which might limit those rights. See, H.R. Rep. No. 2222, 60th Cong., 2nd Sess., p. 7. Now, these newly protected musical compositions could be performed and embodied in sound recordings (although sound recordings were still not protected by federal law at this time), which could themselves be performed in broadcasts over the radio waves. It was an exciting time in the music business, which saw the rise of music publishers, record labels, radio stations, Harry Fox and all three performance rights organizations, ASCAP, SESAC and BMI, in that order.

The industry became a powerhouse. The radio stations played the sound recordings, inspiring their listeners to buy the product distributed by the record labels. The performance rights organizations would collect the royalties for performance of the musical compositions, and pay the music publishers and the songwriters. Everyone was happy, or so it seemed. Still there were flaws in the system. The sound recordings – the the actual performances of a musical compositions fixed onto records – would not receive copyright protection for another 60 years when Congress passed the Sound Recording Amendment of 1971, and even then received only limited rights: derivative, distribution and reproduction. Five years later, the Copyright Act of 1976 created a specific category for sound recordings, and Congress has since given the authors of sound recordings the right to receive digital performance royalties, although they are still not entitled to terrestrial performance royalties, as are songwriters and publishers.

So, prior to February 15, 1972 when the SR Amendment took effect, the performances of the featured artists and musicians on those recordings were not entitled to any performance royalty, but rather were only paid the meager artist royalties that they received from the record labels, if they received anything at all. That deficiency left a significant gap for sound recordings created from circa 1874 until 1972, which were only protected under state and common law regimes – varying widely from state to state if they are even recognized at all – containing divergent scopes of protection, limitations and exceptions. Many attempts have also been made by the recording industry and other stakeholder to urge Congress to pass such acts as the Fair Play Fair Pay Act (H.R. 1836) which would add terrestrial royalties to their list of rights and revenue streams.

As may be expected, this kind of legislative confusion has led to a great deal of state lawsuits as creators of pre-1972 sound recordings attempt to enforce their rights through state courts. In one such case brought by my good friend, Mark Volman of the Turtles, a court ordered SirrusXM to pay almost $100 million to settle a class action lawsuit brought in California, Florida and New York based on state laws governing pre-1972 recordings. In a similar case, the internet service Grooveshark had its business model decimated and was finally forced into bankruptcy as a result of its fight against labels over its use of pre-1972 recordings and whether the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s safe harbor provision applied.

Such high-profile lawsuits often motivate legislators, who are in turn motivated by what motivates their constituents. As a result, last month, Congressmen Jerrold Nadler (D-NY) and Darrell Issa (R-CA) of the 115th Congress introduced House Resolution 3301, the CLASSICS Act, an acronym for the Compensating Legacy Artists for their Songs, Service, and Important Contributions to Society Act. See, the full text here. The bill has six sponsors, among them is Tennessee’s Representative from the 71st District, Marsha Blackburn.

While the bill addresses the orphan status of pre-1972 gap sound recordings by providing them with the rights currently enjoyed by post-1972 recordings (i.e., reproduction, distribution, digital performance, and derivative rights), it stops short of full federalization of those recordings and continues to ignore the terrestrial royalty issue. The CLASSICS Act is short by today’s standards, addressing only a few key points. Nonetheless, it is a step in the right direction.

In short, the CLASSICS Act addresses two of the significant issues raised by the two examples of litigation cited earlier: it makes very clear that the rights of pre-1972 sound recordings are on parity with later sound recordings; and that the DMCA notice and takedown regime is applicable. Notably, Section 1401(d)(1) of the CLASSIC Act “shall not be construed to annul or limit any rights or 9 remedies under the common law or statutes of any State for sound recordings fixed before February 15, 11 1972.” In other words, state law claims are still permissible.

H.R. 3301 is still “only a bill,” and is, as of now, “sitting [t]here on Capital Hill.” As we learned from Mr. Bill in that School House Rock classic written by Dave Frishberg and performed by Jack Sheldon, “it’s a long, long wait while [it’s] sitting in committee,” but a least we can “hope and pray” that one day it’ll be a law! You can follow whatever progress it makes on Congress.gov.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]