Apple has spun a very integrate and systematic marketing web in its ill-advised stand against the FBI in the San Bernardino terrorism case. The San Bernardino case is the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil since the 9/11 attacks. The terrorists were killed and the government needs information on one of their smartphones to discover evidence of the terrorist cell.

Apple’s flawed reasoning for withholding assistance in building a case against the terrorists, however, is filled with misinformation and outright lies. Apple has mounted a campaign that attempts to mold the facts to support a better image for Apple, one that has been fading since the death of its founder and cheerleader, Steve Jobs.

Apple is, of course, no stranger to spreading marketing that inaccurately portrays their products and company in a good light. They have successfully convinced an entire generation into thinking they built the first smartphone when, in fact, smartphones of varying degrees have been around for years prior to the release of the iPhone. Every innovation that Apple conceives is portrayed as the first. Some might argue here that Apple just does it better, simpler, more stylish, etc. – and that admittedly may very well be true – but the facts seem to point to the conclusion that Apple is, for the most part, a follower in most of the actual technologies that it exploits.

So how does this tie in to the San Bernardino shootings and Court Order issued against them? The positions that Apple is taking in its refusal to comply with the court order are rooted in the same arrogance. Apple is portraying itself as the defender of data security and privacy in an effort to skirt the real issues.

The allegations of arrogance are clearly seen in Apple’s own “Message to Our Customers” posted February 16, 2016, beginning in the first paragraph:

The United States government has demanded that Apple take an unprecedented step which threatens the security of our customers. We oppose this order, which has implications far beyond the legal case at hand. This moment calls for public discussion, and we want our customers and people around the country to understand what is at stake.

The very first sentence of Apple’s plea is false. First, the step being ask of Apple in this case is decidedly not “unprecedented.” The FBI is asking for Apple’s assistance to “bypass or disable the auto-erase function” and “enable the FBI to submit passcodes” to the terrorist’s phone. Apple itself admits that it has complied with many such orders in the past, at least 70 times according to the FBI. This led to many allegations on the web from Apple-automatons blindly following their appointed savior, who suggest that the FBI is lying, as here.

It is actually Apple who is spreading the most lies regarding this issue. In a second statement in the February 10th message, Apple claims that “the FBI wants us to make a new version of the iPhone operating system, circumventing several important security features, and install it on an iPhone recovered during the investigation.” They claim that the new “operating system” would be a “master key, capable of opening hundreds of millions of locks – from restaurants and banks to stores and homes.” Really? That’s ballsy even for Apple.

What the government is asking is very clearly laid out in the judge’s Order of February 16, 2016 (note that, not coincidentally, this is the same date that Apple released its open statement). Instead of a “new version of the iPhone operating system,” Judge Pym ordered Apple to create a Software Image File that could be side loaded onto the terrorist’s iPhone. In complete denial of Apple’s claims, Paragraph 3 of the order specifically says “the SIF will load and run from Random Access Memory (“RAM”) and will not modify the iOS on the actual phone. . . .” Further, the judge says that the SIF will contain a “unique identifier of the phone so that the SIF would only load and execute” on the terrorist’s iPhone.

Apple lies are not limited to the current marketing campaign presented to the public, but permeate the testimony it has given in this and the New York case involving a similar fact pattern. In that case, Apple Senior VP of Worldwide Marketing said that it is literally “impossible” to unlock the current operating system on the iPhone.

Most of the families of the 14 victims in the attack have pleaded with Apple to comply with the order so that the government can bolster their case against the perpetrators, Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik, but those pleas have fallen on deaf ears, weakening the company’s assertions that they are “shocked and outraged” by the terrorist attack. Apple finds itself in the awkward position of being the underdog in its claims, as over 50% of the American public believes that they should comply with the order. Most also believe that assisting the FBI will have little or no effect on the security of personal data on other iPhones.

But that doesn’t mean that the unfounded marketing campaign isn’t effective. Several high ranking officials in both government and industry support Apple’s stance, for differing reasons and motivations. For example, one Congress person who should know better, Rep. Anna Eshoo, a ranking Democratic member of the Congressional Communications and Technology Subcommittee, ignores legal precedent in her assertion that “what Congress would not legislate, the FBI is now seeking to accomplish through the courts.” She quotes the now decease Supreme Court Justice, Antonin Scalia, who stated in Arizona v. Hicks, that “the Constitution sometimes insulates the criminality of a few in order to protect the privacy of all” in support of her position. Of course, in doing so, she thumbs her nose at her Commander-in-chief, Barrack Obama, who came out in support of the FBI’s position. In addition, Scalia’s statement should be taken in the context that such instances are rare when the rights of the few outweigh the rights of the many. Yes, there are times when that is the case, but our laws are built on the utilitarian principles that “what is good for the many is good for the few,” not the other way around.

The exaggerated claims of Apple’s key officials are perhaps best neutralized by the comments of Bill Gates, founder of Microsoft, on the subject, who recognized the FBI’s request as fairly routine. “Apple has access to the information, “they’re just refusing to provide access. . . . You shouldn’t call the access some special thing,” Gates said, in an obvious reference to their allegations that the government is asking them to build an entirely new operating system. Gates compared the FBI’s request to a search warrant issued against a bank or some other third party who possesses sensitive information. “There’s no difference between the information.”

Gates is alluding to the fact that courts have allowed search warrants in the past on all types of data contained in all sorts of format, including digital: banks, medical records, financial information, smartphones, etc. Requiring a bank to release financial information of one customer does not have any impact on the date of millions of other customers.

The statement of FBI Director, James B. Comey, confirms as much:

“We simply want the chance, with a search warrant, to try to guess the terrorist’s passcode without the phone essentially self-destructing and without it taking a decade to guess correctly,” Comey wrote on the website Lawfare, a prominent national security law blog. “That’s it. We don’t want to break anyone’s encryption or set a master key loose on the land.”

The real question here is what gives Apple the right to refuse to comply with a court order? What gives the company the right to become a standard bearer for digital privacy at the expense of our country’s security. No ordinary citizen would be entitled to refuse the court’s request without being subjected to criminal contempt charges and be locked in prison. If the officers of Apple continue in their refusals to comply, the same should happen to them.

By all accounts, Farook and Malik were part of a “homegrown, self-radicalized [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][group of] individuals operating undetected before striking one of many soft targets in the U.S.,” according to the New York Times. The FBI has already uncovered and arrested at least one additional member of this terrorist cell, Enrique Marquez, Jr., their next door neighbor. The FBI and the San Bernardino County District Attorney, Michael Ramos, confirmed that their believed the iPhone in question belonged to Farook and was used to communicate information about the attack. They further believe it will contain evidence of a possible third shooter as well as a “dormant cyber pathogen,” i.e., malware, that could have been released into the government’s computer networks.

Knowing this, would not any reasonable person say that the needs of the people of the U.S. demand that Apple comply with the court’s order? The information is desperately needed to avert future attacks on U.S. soil and to prevent the spread of further terrorism. Apple responds that if they comply, the government “would have the power to reach into anyone’s device to capture their data” and “extend this breach of privacy and demand that Apple build surveillance software to intercept your messages….” That is simply not true.

Apple’s entire argumentative response falls squarely into the classical logical fallacy of the “straw man” argument, which attempts to refute a given proposition by showing that a inaccurate form of the proposition (the “straw man”) leads to absurd, unpleasant, or ridiculous consequences. Here, Apple sets up the argument that the FBI is requesting that they build a new version of the iOS, which will lead to unchecked government surveillance. The straw man argument relies on the audience failing to notice that the argument does not actually apply to the original proposition. In this case, all of Apple’s assertions contradict the actual language of the Court’s February 16th Order. Read it for yourself and see if you agree. The Court’s order applies only to the single terrorist’s iPhone5 and does not ask Apple to build a new iOS for the phone. This is the kernel of untruth that Apple is spreading through its marketing prowess.

The fact remains that Apple’s refusal to comply with the Court’s order is both arrogant and criminal. They’re not selling iPad’s or iPhone’s here – it might be forgivable to spread false marketing claims in order to sell products, that’s the American way – rather, Apple is plainly impairing the ability of the U.S. people to defend themselves against terrorist attacks in the name of protecting the privacy of individuals, and that’s not American. It’s time for Apple to do its civil duty and comply.

gy.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

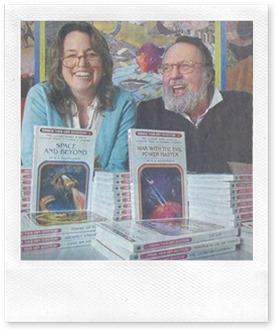

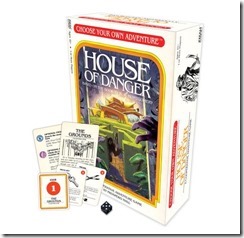

More recently, in January of 2019, Chooseco instituted a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against streaming giant, Netflix, for several causes of action relating to trademark and trade dress infringement. Chooseco claims that an episode of Netflix’s show Black Mirror, which feature a young programmer who creates an adventure video game called Bandersnatch based on a “choose your own adventure” book of the same name, infringes and dilutes the Mark.

More recently, in January of 2019, Chooseco instituted a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against streaming giant, Netflix, for several causes of action relating to trademark and trade dress infringement. Chooseco claims that an episode of Netflix’s show Black Mirror, which feature a young programmer who creates an adventure video game called Bandersnatch based on a “choose your own adventure” book of the same name, infringes and dilutes the Mark.  like Bandersnatch receive special protection from trademark litigation under the First Amendment – think Andy Warhol’s use of the Campbell soup can or Marilyn Monroe’s image. Under the cited Second Circuit case, Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994 (2d Cir. 1989), for example, the use of a trademark in an artistic work is constitutionally protected unless it either “has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever, or explicitly misleads as to the source…of the work.” The threshold for proving that a work has at least some artist relevance to the underlying work is extremely low and should easily be satisfied by Netflix in this case.

like Bandersnatch receive special protection from trademark litigation under the First Amendment – think Andy Warhol’s use of the Campbell soup can or Marilyn Monroe’s image. Under the cited Second Circuit case, Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994 (2d Cir. 1989), for example, the use of a trademark in an artistic work is constitutionally protected unless it either “has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever, or explicitly misleads as to the source…of the work.” The threshold for proving that a work has at least some artist relevance to the underlying work is extremely low and should easily be satisfied by Netflix in this case.

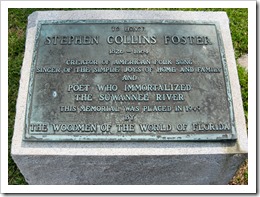

ons. In the mid 1800’s, when Stephen Foster wrote The Suwannee River, Oh! Susanna, Camptown Races, Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair, and Old Kentucky Home, the 1790 Copyright Act only protected “maps, charts and books” and thus did not extend to musical compositions. The only way Foster could conceive of earning an income from his craft was to sell his sheet music to traveling troubadours and minstrel shows, such as “Christy’s,” that traveled the country. The strategy worked in terms of getting his music exposure, but without adequate protective remedies, it created an environment where unscrupulous and dishonest publishers “bootlegged” his work and sold copies for their own profit. While most of the country knew Foster’s work (even today) because of this exploitation, he died a pauper in 1864 with less than a dollar to his name. So much for the post-Napster argument that illegally downloading and streaming music actually makes money for its creator by giving it wider exposure!

ons. In the mid 1800’s, when Stephen Foster wrote The Suwannee River, Oh! Susanna, Camptown Races, Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair, and Old Kentucky Home, the 1790 Copyright Act only protected “maps, charts and books” and thus did not extend to musical compositions. The only way Foster could conceive of earning an income from his craft was to sell his sheet music to traveling troubadours and minstrel shows, such as “Christy’s,” that traveled the country. The strategy worked in terms of getting his music exposure, but without adequate protective remedies, it created an environment where unscrupulous and dishonest publishers “bootlegged” his work and sold copies for their own profit. While most of the country knew Foster’s work (even today) because of this exploitation, he died a pauper in 1864 with less than a dollar to his name. So much for the post-Napster argument that illegally downloading and streaming music actually makes money for its creator by giving it wider exposure!

to having previously heard the work.

to having previously heard the work.