By guest student writer, John Freund

Music production is simply not what it used to be. Behind every great record is great production, but just what that production entails continues to grow more complex with new technology and a changing music industry.

During its humble beginnings in the mid-20th century, production was extremely simple, quick, and required only a small handful of people. Artist and Repertoire (A & R) men personnel would discover and contract talent, record the m usicians with several microphones in several sessions, mix the project together and complete the mastered tracks in a few days[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][1].

usicians with several microphones in several sessions, mix the project together and complete the mastered tracks in a few days[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][1].

As the digital age arrived and production became more complicated and technologically demanding, it also required engineers, technicians, and a head record producer to guide the creative process of making an album through the tedious responsibilities involved.

Today, with digital audio workstation software like ProTools, GarageBand, and Logic replacing much of the work of a recording studio for a minimal fraction of the cost, production is being transformed yet again.

Since the dawn of the 20th century, sound recording and studio production in the music industry have been completely revolutionized due to major advances in audio recording technology. The first and most significant development in audio recording technology was Thomas Edison’s invention of the phonograph in 1877[2]. For the first time in history, people could enjoy sound without a live performance, and musical compositions could be preserved not only on paper, but in recordings as well. As the technological marvel began to catch on in American homes in the early 20th century, citizens could now choose what music they wanted to hear, when they wanted to hear it, and how many times to repeat any given song[3]. This new ability to preserve music would lead to a number of radical new facets of the music industry, such as collecting, broadcasting, producing, engineering, sampling, synthesizing, and manipulating sound – as well as manufacturing, distributing, and retailing physical reproductions of the recording. It also placed new demands and limits on composers, who had previously composed their music for sheet music. As 20th century composer Igor Stravinsky noted, “In America I had arranged… to make records of some of my music. This suggested the idea that I should compose something whose length should be determined by the capacity of the record”3. As Stravinsky composed to fit the length of a record, so too have countless musicians composed with a record or production in mind, rather than a live performance or sheet music. All of these new fields stemmed from the ability to record sound, and the world of music would never be the same.

Another notable development in recording technology was the stereophonic recording that replaced monophonic sound. First released to the public in the 1950s, the trend began to spread in the next several decades as recording became more advanced. Monophonic sound was ultimately forgotten (with some exceptions) and stereophonic sound, or “stereo,” became the standard. Using two audio channels instead of one and blending them together allowed producers to create the first versions of surround sound – closer to natural hearing, music in stereo is heard from both directions. Panning the audio tracks between left and right channels became a standard part of mixing, and is still in widespread use today.

As the century progressed and the stereo record player saturated the market, record labels such as Columbia Records, Decca Records, and Edison Bell replaced sheet music publishers as the solid base of the music industry.[4] The prominence of recordings gave rise to a new process, and eventually a new line of work: studio recording and production.

It was at this time that recording studios began popping up in Nashville, New York, and other American cities, and with them appeared new recording technology. Long-playing (LP) albums became the norm as record players were very popular, and the booming radio industry provided even more stimulus to the industry.[5] At this time, record labels hired A & R employees who discovered new talent and often record the talent and musicians at a studio until the track was mastered. The simplicity of the recording process at this time allowed a typically unofficial producer to record musicians on one track1.

So, tThe roll of the producer has come a long way since the 1950s and 1960s. What was once a simple task practiced by any sound-tech is now its own specialized profession.

Phil Ramone, a successful producer who began his career in the 1960s, offers his opinion on the production process: “There’s a craft to making records, and behind every recording lie dozens of details that are invisible to someone listening on the radio, CD player, or iPod.”1.

The first of these groups of details is the multi-track recording process. Recording music onto a 1 or 2-inch tape, producers could synchronize multiple music tracks next to each other on the same tape, thereby making music recordings more complex. Multi-track recording using tapes replaced single-track recording as the most popular way and then thrived with the introduction of cassettes in the 1960s.[6] Producers and engineers also began to splice sounds together from different tapes into one new tape that would be used in the music project.[7] Multi-track tape recorders also launched one of the most detailed aspects of a recording process – mixing. Mixing took advantage of the new recording technology by allowing producers to set separate levels for each track and add effects and processors. Mixing is the tedious and intricate stage of studio production that falls between the recording and the mastering. The complexities of the entire production process changed the quality music and held record producers to a higher standard.

Club music listeners and Disco lovers desired a crisp, pristine sound that required detailed mixing work and talented audio engineers[8]. During this time, some artists began involving themselves in production and becoming more knowledgeable in the studio, producers became even more valuable because of their expertise and objectivity.1 This expertise furthered the producer’s roll as a creative guide to the artist and general overseer of studio projects. They took on responsibilities and asks, such as selecting and arranging songs, controlling and guiding the musicians and workers in the studio, and seeing the project through each stage to its completion and perfection.9 Again, in the words of Phil Ramone,

“Someone’s got to think fast and move things ahead, and those tasks fall to the producer. Because he or she is involved in nearly every aspect of a production, the producer serves as friend, cheerleader, psychologist, taskmaster, court jester, troubleshooter, secretary, traffic cop, judge, and jury rolled into one.”1

After the cassette tape and multi-track recording, the next major technological breakthrough in the music industry came in the form of compact discs (CDs) and personal computers (PCs), which made their mainstream arrival in the 1980s. In 1982, Sony released “52nd Street” by Billy Joel as the first of a set of fifty CD titles.10 While the CD did not catch fire with the average consumer until late in t he decade, the revolutionary technology and widespread usage of computers across America soon transformed the way music was recorded, produced, and distributed. Approximately one hundred years after Edison’s phonograph, producers could finally store music digitally. CDs gave for more storage capacity than cassettes, and the ability for listeners to skip to any track instead of rewinding or fast forwarding. Also, this digital audio technology helped producers and engineers make accurate adjustments to any specific point on the track. This improved the quality of mixing and mastering, while also streamlining the production process.

he decade, the revolutionary technology and widespread usage of computers across America soon transformed the way music was recorded, produced, and distributed. Approximately one hundred years after Edison’s phonograph, producers could finally store music digitally. CDs gave for more storage capacity than cassettes, and the ability for listeners to skip to any track instead of rewinding or fast forwarding. Also, this digital audio technology helped producers and engineers make accurate adjustments to any specific point on the track. This improved the quality of mixing and mastering, while also streamlining the production process.

Similarly transformative to the CD and another component of the computer was Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) technology. As the synthesizers of the 1970s were being used in cooperation with the compact computers of the early 1980s, domestic and foreign companies alike competed for the latest digital music and synthesizer technology. These synthesizers were utilized by many popular acts of the day, such as Paul McCartney, Duran Duran, The Who, and Herbie Hancock.11 Rather than transmitting an audio signal, MIDI spoke a digital language that enabled synthesizers and computers to connect with a MIDI controller or sampler. This language, or protocol, became universally accepted as a form of audio communications11. In other words, MIDI allowed people to manipulate a sample of one sound or bank of sounds, produce audio signals of the samples played at specific pitches and tempos with specific effects and sounds. This process of recording music using MIDI is called sequencing, and today, is the foundational idea of computer music notation software (also known as digital audio workstations). 12 People have made millions of sounds using MIDI technology, and it has been a key component of modern music for almost thirty years, making way for new genres, new software, and new engineering. MIDI is also used to create recordings that recreate a live sound. Paul Théberge offers this opinion of MIDI in saying, “…apparently for some listeners MIDI sequencing virtually returns the ‘aura’ of live musical performance to the medium of digital reproduction.”12 With the possible exception of the phonograph, MIDI has made the greatest impact on audio recording technology.

While computer and MIDI synthesizing were digitalizing the way music was produced, another digitally-based change was taking place. Many studios transitioned from the traditional analog mixing console to new digital mixing consoles. Early mixing consoles of the 1950s controlled few channels, while the new, massive digital consoles could meticulously control hundreds of channels if desired.13 In addition, mixing levels and settings could now be saved digitally, which was especially handy for live production and touring. The analog vs. digital mixing console debate is a heated one today, as many producers and technicians prefer analog consoles, the digital consoles are gaining popularity in today’s market.

Following the CD was the groundbreaking digital audio file which provoked yet another change in how music is consumed and produced. Streaming and downloading music from the Internet is today’s most popular music technology. The arrival of the MP3 made it easier for consumers to transfer music from CDs to computers14. CD-ROM drives in computers allowed for countless music listeners to share music with each other through ripping, burning, and transferring music files. Production came into play as more music was produced on computers, and digital audio medium knowledge was necessary to avoid losing part of the recording sound while creating such a file (8). With every new bit of technology, top-quality production requires more and more expertise than ever before. However, in today’s digital age, countless production projects are completed on personal computers without an ounce of expertise.

An astute view on the present and future trends of production, is provided by DJ, artist, and producer Moby in an interview with Lucy Walker:

The way that music is made has changed completely and it will continue to change. It’s become so much more egalitarian, democratic, and inexpensive. The way that music is sold, distributed, listened to. The role that music serves in most people’s lives. One the one hand music is so much more ubiquitous, but on the other it’s so much cheaper. So, making predictions – I have no idea. The only prediction I can make is that music has become so much more egalitarian and ubiquitous and the means of production have become available to almost anybody. Anyone with access to a computer can make music now. You download the software from the Internet and ten minutes later you’re making music that sounds just as good as anything you might hear in a nightclub[9].

Many artists choose to compose and record at home, opting to pay a few hundred dollars for solid recording software rather than employ the costly services of a professional studio. Some recording software, like the popular program Audacity, is available for free online, and as software technology progresses, it grows closer in quality to the sound of professionally recorded, mixed, and mastered music, making recording even easier for the home artist. Moreover, The American Home Recording Act, passed in 1996, specifies that computers are not recording devices, thereby releasing home studios from having to pay expensive royalties like a professional studio with professional recording equipment.14 All genres of music can be made on a computer, although some production-oriented genres (like techno and hip hop) thrive more than others in digital production.14 This new trend has shifted many projects from the studio to the computer and has also paved the way for new, smaller projects unaffiliated with a studio or label. The ease at which an artist can now record, mix, and master his or her own work grows each day, and music made in an unprofessional studio can often be hard to distinguish from its professional counterpart. Digital distribution through iTunes and other services has simplified the distribution process and allowed anyone to share their music with others for a small charge or none at all, further driving away the need to go through a studio and label distribution. For production studios and producers, as well as the entire record industry, this digital audio workstation availability has been harmful to businesses by reducing sales. As author Buskirk Eliot Van points out, “Computers mean fewer trips to the music store, since they can assume most of those functions. Granted, they will never replace guitars and other physical instruments, but thanks to sampling and music creation software, they come closer each year.”14 Music stores themselves are beginning to sell more digital music production hardware and software, as more and more customers are leaning towards computerized equipment.

Overall, audio recording technology has had a tremendous impact on the way music is recorded and produced. The roles of producers, studios, record labels, computers, and other such recording components have been rapidly changing throughout the last century, and will continue to morph along with the entire music industry. Many inventions, from the phonograph to MIDI, have re-defined the recording process. The industry has seen its mediums develop from discs and cylinders on phonographs, to LPs, cassette tapes, CDs, and digital audio files. Studio recordings have expanded from single-track monophonic sound to digital stereophonic sound with hundreds of channels and tracks. Virtually every process of composing, recording, and producing music can now be performed digitally on computers, and the ability to perform these processes is inexpensively available to the masses more than ever before. In the words of Phil Ramone,

“The greatest interaction in the world is the creativity involved in making music.”1

With vast accessibility and increasingly complex production tools in today’s incredible technology, there has never been more potential for creativity in music making. For as long as music is created and recorded, how it is made will be just as interesting a topic as the music itself. As continuously innovative as progressive rock, and as unpredictable as a jazz saxophone solo, the process of how music is captured will never stop changing.

With vast accessibility and increasingly complex production tools in today’s incredible technology, there has never been more potential for creativity in music making. For as long as music is created and recorded, how it is made will be just as interesting a topic as the music itself. As continuously innovative as progressive rock, and as unpredictable as a jazz saxophone solo, the process of how music is captured will never stop changing.

John Freund is a working towards a degree in music business at Belmont University’s Mike Curb School of Music Business in Nashville, Tennessee. This article is adapted from the a final paper John wrote for Professor Shrum’s Survey of Music Business class as freshman in the fall semester of 2010. John is from New Jersey where he is currently working as busboy at Daddy-o’ on the Jersey shore, having a great summer break!

[1] Ramone, Phil, and Charles L. Granata. Making Records: the Scenes behind the Music. New York: Hyperion, 2007. Print: 15, xi, 9.

[2] "The Phonograph, 1877 Thru 1896." Scientific American (1896). Machine-History.Com. Web. 05 Dec. 2010: ¶ 1.

[3] Katz, Mark. Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music. Berkeley: University of California, 2004. Print: 9, 3.

[4] Shrum, Barry. “Record Industry Introduction.” Survey of Music Business. Belmont University. Nashville, TN. 15 Sept. 2010. Class Lecture.

[5] Shrum, Barry. “Brief History of Broadcasting.” Survey of Music Business. Belmont University. Nashville, TN. 04 Oct. 2010. Class Lecture.

[6] Morton, David. Sound Recording: the Life Story of a Technology. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2004. Print: 141.

[7] McIntyre, Allyson L. Music Technology and the Twenty-First Century Compose: Are Computer-Assisted Notation Programs Becoming More of a Crutch Than a Tool? Compositional Concerns in the Technological Age. Diss. Belmont University, 2004. Nashville, TN, 2004. Print: 2.

[8] Moorefield, Virgil. The Producer as Composer: Shaping the Sounds of Popular Music. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2005. Print.

[9] Miller, Paul D., ed. Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture. Cambridge,

MA: MIT, 2008. Print: 155.

Further Reading

"Do You Know The History Of The Mixing Console?" Music Magazine 69. 02 Nov. 2010. Web. 06 Dec. 2010F

Katz, Mark. Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music. Berkeley: University of California, 2004.

Manning, Peter. Electronic and Computer Music. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. Web. 05 Dec. 2010.

McIntyre, Allyson L. Music Technology and the Twenty-First Century Compose: Are Computer-Assisted Notation Programs Becoming More of a Crutch Than a Tool? Compositional Concerns in the Technological Age. Diss. Belmont University, 2004. Nashville, TN, 2004.

Miller, Paul D., ed. Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2008. Print.

Moorefield, Virgil. The Producer as Composer: Shaping the Sounds of Popular Music. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2005.

Morton, David. Sound Recording: the Life Story of a Technology. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2004.

"The Phonograph, 1877 Thru 1896." Scientific American (1896). Machine- History.Com. Web. 05 Dec. 2010.

Ramone, Phil, and Charles L. Granata. Making Records: the Scenes behind the Music. New York: Hyperion, 2007.

Shrum, Barry. “Brief History of Broadcasting.” Survey of Music Business. Belmont University. Nashville, TN. 04 Oct. 2010. Class Lecture.

Shrum, Barry. “Record Industry Introduction.” Survey of Music Business. Belmont University. Nashville, TN. 15 Sept. 2010. Class Lecture.

Shrum, Barry. “Studios, Musicians, Engineers, and Producers.” Survey of Music Business. Belmont University. Nashville, TN. 27 Sept. 2010. Class Lecture.

"Sony History." Sony Global. Web. 05 Dec. 2010. Théberge, Paul. Any Sound You Can Imagine: Making Music/consuming Technology. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan UP, 1997.

Van, Buskirk Eliot. Burning down the House: Ripping, Recording, Remixing, and More! New York: McGraw-Hill/Osborne, 2003.

[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

ican support and control, there is much more optimism. The Bill, introduced by Congressman Doug Collins (R-Ga), seeks to amend Section 114 and 115 of the Copyright Act to implement some of the suggestions proposed by the Copyright Office’s report. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), a senior senator and member of the critical Judiciary Committee, co-sponsored the legislation and has frequently been an advocate for songwriters. For one thing, it would allow the royalty courts to adapt the “fair market rate” standards when setting mechanical license rates under Section 115, and allow them to consider royalties paid to recording artist when setting rates for songwriters under Section 114. Most people believe that this would be a more profitable structure for songwriters and music publishers.

ican support and control, there is much more optimism. The Bill, introduced by Congressman Doug Collins (R-Ga), seeks to amend Section 114 and 115 of the Copyright Act to implement some of the suggestions proposed by the Copyright Office’s report. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), a senior senator and member of the critical Judiciary Committee, co-sponsored the legislation and has frequently been an advocate for songwriters. For one thing, it would allow the royalty courts to adapt the “fair market rate” standards when setting mechanical license rates under Section 115, and allow them to consider royalties paid to recording artist when setting rates for songwriters under Section 114. Most people believe that this would be a more profitable structure for songwriters and music publishers.

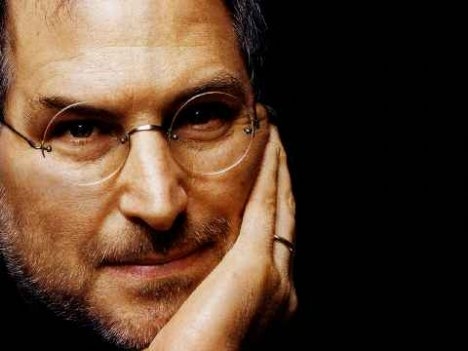

business. You know, great things in business are never done by one person. They’re done by a team of people.

business. You know, great things in business are never done by one person. They’re done by a team of people.

![59418_1389751913862_1534020024_30892[1] 59418_1389751913862_1534020024_30892[1]](http://lawontherow.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/59418_1389751913862_1534020024_308921_thumb.jpg)