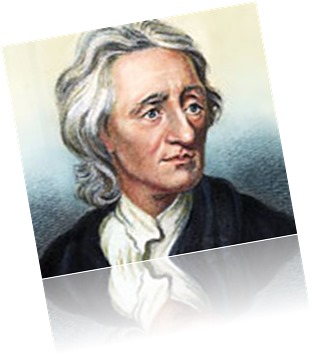

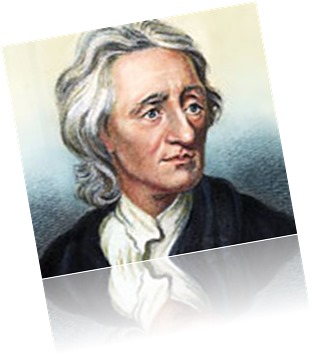

[E]very man has a property in his own person. This nobody has any right to but himself. The labour of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his….”[1] John Locke – a political and social philosopher of 17th Century Enlightenment England and the father of “Classical Liberalism” – was the most influential advocate of natural rights and social contract theory. He believed that in order to establish a civil society, men must give up some of their natural power to the society in exchange for the guarantee of their God-given natural rights. A civil and just government must become a type of “social watchdog” that is charged

with the protection of the individual’s inalienable rights, including, life, liberty and property. These concepts, inspiring in thought and revolutionary in action, were the single most important influence that shaped the founding of the United States. Influenced by Lockean thought, intellectual property – the products of the mind – possessed a value that arose during the framing of both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution and would later influence modern day copyright law.

Locke directly influenced the author of the Declaration of Independence and the framers of the Constitution with his central political principle that rights in property are the basis of human freedom and government exists to protect them and preserve public order. Locke’s theory stemmed from the commonly accepted concept of “Natural Law” under which it was believed that every person has natural rights, not given by a ruler but rather derived from a higher power which, in the case of Locke, was the God of the Bible. These rights, according to Locke, were “inalienable,” i.e., they cannot be taken away.

In Locke’s understanding of Natural Rights, the right of property is paramount. For him, “property” encompassed not only physical possessions, but intellectual capital as well. Locke proposed that within any organized community, there is a type of “Social Contract” between all members of the community in order to gain collective advantages that the members of the body politic would not be able to secure individually. This contract forms the basis of the equitable distribution of rights and obligations between the people and their government. The political power of the government is granted to it by the people and is, therefore, a “trust” for the benefit of the people. In turn, the people give this power so that their own welfare is increased and their individual property is protected in a way not possible in what Locke calls the “State of Nature,” where the will of the stronger (or the many) is often forced upon the will of the weaker (or the few).[2]

Locke’s ideals of the “Contract of Society” and “Contract of Government” formed the basis of Thomas Jefferson’s passionate believes conveyed clearly in the Declaration of Independence:

“We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. – That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –“[3]

Having been bound by the monarchy, Jefferson understood the importance of this radical, yet equitable and sensible, way of thinking. Locke’s ideas were widely circulated and debated throughout the Colonies by this point, and Jefferson would later confess that while writing the Declaration, he “…did not consider it a part of my charge to invent new ideas, but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject.”[4] Jefferson admits to referencing Locke and simply being the tool to communicate and apply the sensibility to the newly independent colonies.

Locke’s influence on American principals can also be seen in his work, A Letter Concerning Toleration. In it, he develops a means of understanding moral truths with strong political implications. Although

his letter focuses primarily on the separation of church and state (something that also had a great impact on Jefferson), it has wider implications in that it provides the philosophical foundation for free speech and freedom of action that follows from free and independent thought. This, in turns, provides a basis for a future understanding of the protection of independent thought as intellectual property. The only precondition of thought, truth, creativity or innovation is political freedom. While in Locke’s letter this freedom of thought refers to specifically to religious ideas, it clearly develops the principal that government is not in the business of enforcing morality but rather protecting an individual’s personal rights from being violated by the collective society.

In a society governed by Locke’s social contract, then, laws established by the government are intended to provide safety and security of the commonwealth as well as every individual’s goods and person.[5] Later, the newly formed United States would incorporate Locke’s freedoms of expression in the First Amendment of the Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging, the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances”[6] Although the First Amendment, just like Locke’s letter, does not reference ownership of property, it will be referenced time and time again in court rulings securing our freedoms of expressions, and will play a crucial role in the development of copyright law in America.

A year after writing the letter referenced above, Locke published the Second Treatise On Civil Government. In it, Locke wrote that the basis of the equality, independence and ultimately the freedom that exists between all individual men, is their mutual possession of reason. He asserted that through Natural Law, God has given the world to every man in common and he has given them reason to make use of it to the best advantage of life and convenience.[7] This is reflected clearly as Jefferson pens the word of the Declaration: “… the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature of Nature’s God entitle them….”[8]

Locke continued to expand on the idea that man has a natural right to take advantage of the Laws of Nature by explaining that the labor of the body or the mind, and the resulting work of the hands, are the property of the individual and anything that nature has provided and man has joined to it makes it his property. Once man has removed it from the common state of nature, mixed it with his physical or intellectual labor, he is therefore annexing it and excluding it from the common right of other men.[9]

Locke further developed these ideas by providing insight into unilateral appropriation, the idea that there is something individuals can do on their own to establish rights over natural resources that others have a moral duty to respect.[10] In American jurisprudence, the idea of unilateral appropriation is used to justify private property rights and morally binding restrictions and limitations that are perhaps with greater authority than any other social agreement, to wit, there is a universal justification for people owning what is theirs. The implication of Locke’s universal appropriation theory is that a person owns his or her labor and any un-owned thing he mixes it with. This labor can improve resources, adding value through the pains of individual labor. Through this labor and improvement of natural resources more natural resources are available for others. Hence appropriators are entitled to some type of unconditional right to produce their own subsistence.[11] In the U.S., Locke’s concepts are incorporated in §102(b) of the Copyright in the form of our “idea/expression” dichotomy, in that a person is free to incorporate common and universal ideas into their own individual expressions.

A little over 100 years later, both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison would embrace the ideology presented by Locke in the Second Treatise, although Jefferson at first struggled with the idea that the protection of intellectual property might somehow become a monopoly and thereby denying others access to a natural flow of information and innovation. This is reflected in a letter to Isaac McPherson on August 13, 1813, often cited by opponents to the concept of intellectual property, in which Jefferson ultimately argues the notion that inventors and their heirs have a natural and exclusive right to their inventions. In the letter, Jefferson insists an idea in nature is excluded from exclusive property stating, “the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of every one, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it.” Jefferson continued that “ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition.” He compares an idea to the air we breathe, “incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation.”

There are two things to note about the famous quotation of Jefferson. First, he clearly notes that it is ideas that exist in nature that cannot be possessed, but implicitly does not stray from the Lockean idea that once a person mixes labor with it it, it can be possessed. He ultimately agrees with Locke that the one who initially possess as well as expresses the idea should have, “exclusive right to the profits arising from them, as an encouragement to men to pursue ideas which may produce utility.”[12] Because of the Colonies’ past experience with England, Jefferson’s principal intellectual conflict over the concept of ideas as property was the threat of monopolizing anything, including intellectual ideas.

Unlike Jefferson, however, Madison, the primary architect of our Constitution, fully embraced the idea of the protection of intellectual property and recognized that the nature of an individual piece of intellectual property is such that it could be useful to all people and yet could be owned by one person. When writing the Fifth Amendment, “No person shall… be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation,” Madison was directly referencing Locke’s idea of appropriation and preservation of their estate[13]

On the other hand, Madison did agree with Jefferson that ownership of property in general could amount to indefinite monopolization of that property by the owner. But Madison nonetheless recognized and later persuaded Jefferson, that intellectual property was a thing of value to all of society and was susceptible of being appropriated in the public interest without just compensation to the individual who was the inventor or author. In Madison’s words “….the (creative) few will be unnecessarily sacrificed to the (greedy)many”[14] (notations added). In these words, Madison ingeniously combined Locke’s idea that a person is entitled to the fruits of their labor as applied to the state of nature with the much more politically accepted notion of utilitarianism that laws should benefit the majority.

So even though Madison sought to protect and provide compensation for intellectual property, he agreed with Locke’s thought that there was a limitation to this protection. Locke describes this limitation as follows: “as much as any one can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils, so much he may by his labor fix a property in. Whatever is beyond this is more than his share and belongs to others.”[15] Although Locke’s comment here refers specifically to tangible natural resources as mixed with the labors of man, the premise is nonetheless later used by Madison when writing, Article I, Section 8, Clause 8, of the Constitution, which provides that “…Congress shall have Power … To promote the Progress of Science and useful arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”[16] This Constitutional provision, birthed in the ideas of Locke in 1690, encapsulated by Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence in 1776, and later drafted into the United States Constitution by Madison in 1788, continues to form the basis for the protection of intellectual property in the United States today.

This is the historical and philosophical evolution of Article I, Section 8, Clause 8, the so-called Progress Clause, which is and always has been the basis for U.S. copyright law. The Progress Clause is the only clause in the Constitution that grants power to Congress and specifies the means to accomplish its stated purpose. The exact limitations of this clause have been the subject of countless U.S. Supreme Court cases. One case in particular, Petrella v. MGM, is a United States Supreme Court copyright decision that references Locke and Madison’s ideas on the limitation of intellectual property ownership. In Petrella, retired boxer Jake LaMotta and his friend Frank Petrella (Plaintiff) wrote a story about his career which resulted in three copyrighted works: a screenplay, written in 1963, the book Raging Bull: My Story, published in 1970 and yet another screenplay, written in 1973.

In 1976, LaMotta and Petrella assigned the copyrights in their works, including renewal rights, to Chartoff-Winkler Productions, Inc., which assigned them in 1978 to United Artists Corporation, which later became a subsidiary of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. In 1980, as a result, MGM released (and registered copyright in) the film Raging Bull, which achieved popular and critical success. Petrella died in 1981, during the initial terms in the three original works (these works will still under the auspice of the 1909 Copyright Act). After his death, the renewal rights in the works reverted to his heirs.

In 1991, Petrella’s daughter sought to renew the copyrights, but was unable to timely file except with respect to the 1963 screenplay. Approximately seven years later, she advised MGM that its exploitation of Raging Bull violated her copyright and threatened suit. Another 9 years after that notification, on January 6, 2009, Petrella finally filed her infringement suit against MGM, seeking monetary and injunctive relief limited to acts of infringement occurring on or after January 6, 2006.

MGM understandably moved for summary judgment, arguing that, under the equitable doctrine of laches, an unreasonable delay by the plaintiff in bringing the claim, Petrella’s 18-year delay in filing suit was unreasonable and prejudicial to MGM. The District Court granted MGM’s motion, holding that laches did in in fact bar Petrlla’s complaint.[17]

In this example, we see the interplay of the Locke/Madison ideology concerning the limitation of intellectual property rights and the checks and balances of our judicial system, and the effect of laches on those rights. Although Petrella fell within her legal right under legislation regarding the transfer of the copyrights, she was stymied by her unreasonable delay in bringing the claim that resulted in her loss. This is an example of how our legal system and doctrines serve to protect the ideas of Locke and our Founding Fathers that there be limits on intellectual property, preventing it from being held hostage for an indefinite period of time.

John Locke is America’s intellectual founding father, imparting knowledge and enlightened thinking to our Founding Fathers and leaving his philosophical fingerprints all over our founding documents. The human right to property, including intellectual  property, was understood by the Framers of the Constitution and evidenced in the Declaration. In order to advance society, the progress of science, creativity and innovation, i.e., intellectual property, must be encouraged with the protection under the law. Although Jefferson argued that thought is free flowing and feared “ideas” might become a monopoly, he had a greater passion for advancing the illumination of minds and the disseminating knowledge through a growing nation. Madison clearly understood that the continuum of existing knowledge to invent and innovate must be protected within the confines of the law so that the newly-created Republican majority didn’t take advantage of the individual’s rights. What began as radical enlightened thinking in the mind of Locke over three hundred years ago, implemented 100 years later by our Founding Fathers when securing the unalienable rights of the people, continues to encourage innovation under the protection of the law over 200 years later.

property, was understood by the Framers of the Constitution and evidenced in the Declaration. In order to advance society, the progress of science, creativity and innovation, i.e., intellectual property, must be encouraged with the protection under the law. Although Jefferson argued that thought is free flowing and feared “ideas” might become a monopoly, he had a greater passion for advancing the illumination of minds and the disseminating knowledge through a growing nation. Madison clearly understood that the continuum of existing knowledge to invent and innovate must be protected within the confines of the law so that the newly-created Republican majority didn’t take advantage of the individual’s rights. What began as radical enlightened thinking in the mind of Locke over three hundred years ago, implemented 100 years later by our Founding Fathers when securing the unalienable rights of the people, continues to encourage innovation under the protection of the law over 200 years later.

The author, Madison Brinnon, is an Entertainment Industry Studies major at Belmont University, minoring in Mass Communication. She will be in Brazil and Argentina during Spring 2015 studying culture and music of Brazil while doing coursework in Music and International Business. Through the summer she travels with the Turtles on their Happy Together Tour as an intern, and returns to college in the Fall at Belmont’s Los Angeles Campus. Ms. Brinnon has also traveled to several countries in Europe and to a small medical clinic in Zimbabwe where she presented medical supplies that she collected through a small philanthropic organization in California that she helped found. Madison indicates that her inspiration for this article, originally turned in as a research paper for Mr. Shrum’s Copyright Law class, was fueled a love for history, especially American History, and states, ”So many times we take our rights for granted and never consider the impact our founding fathers have on our lives today. It is important to understand the foundation upon which modern day law, and in this case, copyright law is based.”

[1]John Locke. Two Treatises on Government. London, 1821. PDF e-book. 209.

[2] George Stephens. John Locke: His American and Carolinian Legacy.” In John Locke Foundation. Raleigh: John Locke Foundation.

[3] “The Declaration of Independence: A Transcription.” National Archives and

Records Administration. Accessed April 14, 2015.

http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration_transcript.html

[4] Richard J. Behn “Declaration of Independence Preparations Drafting Declaration Independence.” Accessed April 13, 2015. http://lehrmaninstitute.org/history/declaration-of-independence.html.

[5] Chuck Braman. “The Political Philosophy of John Locke, and Its Influence on the Founding Fathers and the Political Documents They Created.” 1996. Accessed March 28, 2015. http://www.chuckbraman.com/political-philosophy-of-john-locke.html.

[6] “First Amendment – U.S. Constitution” Findlaw. Accessed April 14, 2015. http://constitution.findlaw.com/amendment1.html.

[7] George Stephens. John Locke: His American and Carolinian Legacy.”

[8] “The Declaration of Independence: A Transcription.” National Archives and

Records Administration. Accessed April 14, 2015.

http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration_transcript.html

[9] Chuck Braman. “The Political Philosophy of John Locke, and Its Influence on the Founding Fathers and the Political Documents They Created.”

[10] Karl Widerquist. “Lockean Theories of Property: Justifications for Unilateral

Appropriation.” Public Reason 2, no. 1 (June 2010): Accessed March 28, 2015.http://www.publicreason.ro/articol/21.

[11] Chuck Braman. “The Political Philosophy of John Locke, and Its Influence on the Founding Fathers and the Political Documents They Created.”

[12] Thomas Jefferson, “Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8: Thomas Jefferson to Isaac McPherson.” Accessed March 28, 2015.

http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/a1_8_8s12.html

[13] “Fifth Amendment – U.S. Constitution” Findlaw. Accessed April 14, 2015.

http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/fifth_amendment.

[14] Howard W. Bremer., JD. “Chapter NO. 3.9 U.S. Laws Affecting the Transfer of Intellectual Property Editor’s Summary, Implications and Best Practices.” Accessed April 09, 2015. http://www.iphandbook.org/handbook/ch03/p09/eo/.

[15] Chuck Braman. “The Political Philosophy of John Locke, and Its Influence on the Founding Fathers and the Political Documents They Created.”

[16] “Article 1, Section 8, Clause 5.” Article 1. Accessed April 14, 2015. https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/article1.

[17] Petrella. v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., (U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals).[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

to sell comics that practically flew off the shelves and in 1989 Ron Perelman purchased Marvel for $82.5 million.

to sell comics that practically flew off the shelves and in 1989 Ron Perelman purchased Marvel for $82.5 million.

Morgan Wisted is an intern at Shrum & Associates and has her own blog at www.silkenraven.com.

Morgan Wisted is an intern at Shrum & Associates and has her own blog at www.silkenraven.com. Notwithstanding that incredibly inconvenient post-mortem

Notwithstanding that incredibly inconvenient post-mortem