The first of the month (August 2016), the Department of Justice issued a summary of findings with regard to two court orders that govern the operation of two of the U.S. performing rights organizations (the “PRO’s”), ASCAP and BMI. If it stands, the decision will also affect the third PRO, SESAC.

Songwriters and music publishers around the country were horrified with the DOJ findings, as were the PRO’s, with many songwriters claiming that they would now have to refrain from co-writing with songwriters belonging to one of the sister PRO’s. This article will examine the logic of the reaction by the music community. Is the proverbial sky falling, or will this event pass into obscurity and irrelevance? We’ll sort out what all this means in this article.

As an aside, if you were not fortunate enough to tune into last night’s episode of my friends Heino and Scott with The Music Row Show on WSM 650, go to their website and check out the archives, as much of the information we share here was talked about in that radio program. My appearance and conversation with The Music Row Show made me realize just how confused many songwriters will be about all of this legal maneuvering.

Background

Before we look at the court orders, referred to as “Consent Decrees,” a little historical background will be helpful. As I said, there are primarily three PRO’s, ASCAP, SESAC and BMI, and they were created in that order. The two largest US PRO’s, ASCAP and BMI, make up the majority of the industry. SESAC, by most accounts, has between 10-20% market share (although it is growing exponentially).

This is because ASCAP and BMI were both created out of controversy and strife and that highly competitive environmental produced some robust and resilient entities. ASCAP arouse out of the Tin Pan Alley days. Several of the key songwriters, IRVING BERLIN, VICTOR HERBERT and JOHN PHILLIPS SOUSA, began to see their songs being performed in restaurants, hotel lobbies and other venues, and they realized that they were not receiving royalties from these performances, a right that was first granted in 1897 and then incorporated directly into the 1909 Act. These famous writers banded together to form the first coalition of songwriters and publisher, the American Society of Authors, Composers and Publishers.

Their efforts may have been received well in the music community, but the entities that used the music did not share that enthusiasm. Certain NYC restaurant and hotel magnets, namely Shanely and Vanderbilt, questioned whether they were required to pay the composer for performance of a song in their establishments, even though they charged no admission for those performances. The music, they maintained, was just a side show and not the main focus of what their customers were paying for.

The case, Herbert et al. v. Shanley et al. went all the way to the Supreme Court. Writing for the majority, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes ruled in favor of ASCAP and songwriters, saying:

Music is part of the total for which the public pays and the fact that the price of the whole is attributable to a particular item which those present are expected to order is not important. It is true that music is not the sole object, but neither is the food, which probably could be got cheaper elsewhere.

As a result, ASCAP had the stamp of approval from the highest court in the land. They started an aggressive campaign to acquire licenses from venues where performances of music occurred, including broadcasters like television and radio stations.

BMI arose as a direct result of ASCAP’s aggressive licensing activities. From 1931-1939, ASCAP increased its royalty rates to radio and television stations over 400%, to the point where a group of broadcasters decided to get together and form Broadcast Musicians Incorporated in 1939. They started signing their own composers and begin licensing non-ASCAP works for their catalog. After a few years, most radio and television stations stopped using ASCAP music and would only use BMI-licensed music.

BMI and ASCAP have been adversaries ever since. ASCAP, of course, had the upper hand, since they were first to market and arose out of the Tin Pan Alley environment. ASCAP did not take kindly to being shut out of the lucrative broadcast market and the two organizations began a decades long fight for the music users. This conflict ultimately caught the attention of the DOJ, who sued each entity under the Sherman Act (anti-trust) to address their comparative market power and balance the weight of power. The result of the DOJ’s involvement were the consent decrees that, to this day, govern how terrestrial radio (Either AM/FM) digital rebroadcasts, and/or venues such as bars and arenas, license the performance of compositions.

BMI and ASCAP have been adversaries ever since. ASCAP, of course, had the upper hand, since they were first to market and arose out of the Tin Pan Alley environment. ASCAP did not take kindly to being shut out of the lucrative broadcast market and the two organizations began a decades long fight for the music users. This conflict ultimately caught the attention of the DOJ, who sued each entity under the Sherman Act (anti-trust) to address their comparative market power and balance the weight of power. The result of the DOJ’s involvement were the consent decrees that, to this day, govern how terrestrial radio (Either AM/FM) digital rebroadcasts, and/or venues such as bars and arenas, license the performance of compositions.

SESAC, a European PRO at first licensing mostly classical, slipped into the U.S. in 1939 amidst all of this sibling rivalry and began licensing in the U.S., but as a private entity as opposed to operating as a non-profit like ASCAP and BMI. They are not subject to any consent decrees and to this day remain under the radar, although the DOJ periodically audits them as well.

The ASCAP/BMI consent decrees defining what the PRO’s can and cannot not do – most notably, it requires them to issue “blanket licenses” to certain users. These have been amended in 2003 and 1994 respectively. The decrees also require that both entities offer licenses are similar terms and to similar clientele. Importantly, for this discussion, the consent decree require that the PRO’s license to a user like Pandora one a request for license is made, regardless of whether a rate has been negotiated. If the PRO’s and the user cannot agree on a rate, it is then presented to the “rate court” set up by the consent decree to decide. The catch is that while all of this legal wrangling is going on, services like Pandora can continue performing the music.

The Recent DOJ Ruling

The gravamen of this issue happened in 2013 when several large music publishers, SONY ATV, EMI and Universal, among others, withdrew their “new media” licensing rights from ASCAP and BMI, leaving them to collect only their terrestrial right (read broadcasted radio or television). They did this for a couple of reasons: first, the consent decree do not allow the PRO’s to negotiate a market rate with digital streaming services; so, secondly, they did it in order to negotiate better deals directly with Pandora. In 2013, Pandora negotiated a favorable percentage rate with Sony and Universal based on their gross revenues.

With their hands tied and major publishers going direct to digital stream services, ASCAP and BMI had no choice. Streaming revenues have been increasing for years, and without these major players bringing in revenue, their revenues were decreasing. So, in short, ASCAP and BMI went back to the DOJ seeking clarification with regard to the consent decrees with regard to operation and effectiveness. Among other things, ASCAP/BMI ask that the decrees be modified to allow publishers/songwriters to “partially withdraw” their works. This prompted a new review of the Consent Decrees by the Department of Justice that begin in 2014. The DOJ released its findings on August 4, 2016 of this month.

The DOJ said that the ASCAP consent decrees doesn’t allow a publisher to withdraw partial shares. It stated that consent decrees require a PRO “license to perform all the works in [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][its] repertory…” That meant, according to the DOJ, that it could not “rewrite the decree” to let publishers pick and choose how works are licensed and allow fractional shares. This has great impact on the existing deals already negotiated with Pandora. Specifically, the DOJ said:

The licensing of works through ASCAP is offered to publishers on a take-it-or-leave-it basis.

Specifically, the DOJ ruled:

1) That the consent decrees would not be modified or abolished

2) That the consent decrees to DO NOT allow “fractional” licenses that convey only fractional shares and required additional (read other PRO) to perform the works, i.e, the DOJ interpreted the consent decrees to require “full-work” licensing.

This new and dramatically different interpretation requires the PRO’s to convey licenses to radio, television, bars and digital music services giving them the right to public perform “100%” of their repertoires without the risk of adverse infringement. This new “full-work licensing” principal applies even if ASCAP or BMI only represent a small fraction of a song’s copyright, which is almost always the case. The problem, of course, is that ASCAP and BMI do not generally have the legal right to convey 100%!

Ironically, the DOJ findings state that “the current status quo system [used by the PRO’s]. . . has served the industry well for decades and should remain intact.” This is confusing, since historically the PRO’s have licensed fractional shares, contrary to the DOJ’s findings. A single song most often is written by multiple songwriters and those songwriters are generally affiliated with different performance rights organizations and only own a fractional interest in that song. When a song such as All-American Girl, is written by Carrie Underwood, whose performance is licensed by BMI, with two other ASCAP songwriters, traditionally BMI would license 33.33% of the song and ASCAP would license the other 66.66%. Now, according to the DOJ, either BMI and or ASCAP would have to license 100% of the song and report and pay the royalties for the other songwriters to the other PRO. Imagine how these historic competitors view that prospect!

Herein lies a big part of this current problem. If we look to copyright law, as we must, the answers may be clearer. Under section 201(a), the author of song is the owner of the song. But as all songwriters in Nashville are prone to collaborate, we have to factor in a second author/owner. When that happens, the copyright law treats each owner as a tenant-in-common, just like two spouses who jointly own a house. In other word, each one owns 100%. So what does that mean?

That means that “[e]ach co-owner may thus grant a nonexclusive license to use the entire work without the consent of other co-owners, provided that the licensor accounts for and pays over to his or her co-owners their pro-rata shares of the proceeds.” United States Copyright Office, Views of the United States Copyright Office Concerning PRO Licensing of Jointly Owned Works (2016). Of course, the songwriters can alter this default situation through signing a collaboration agreement, but no one ever does because that would “harsh the songwriting vibe.”

Furthermore, in a joint author situation, either author of the work may enforce the right to exclude others from using the work. So, each author of a joint work “has the independent right to use or license the copyright subject only to a duty to account for any profits he earns from the licensing or use of the copyright.” Ashton-Tate Corp., 916 F.2d at 522 (9th Cir.1990). Accordingly, a joint copyright owner may not exclude other joint owners or persons who have a license from another joint owner.

But there is another part of this analysis that can’t be ignored, and that is the doctrine of indivisibility. Under the prior, 1909 Copyright Act, the author(s) could NOT divide the copyright, meaning that if the copyright was licensed, the entire copyright had to be licensed, not just one of the exclusive rights. So, I would not be able to issue a print license apart from a license to perform the work. The 1976 Act eliminated this doctrine and effectively made the copyright divisible. Specifically, Section 201(d)(1) of the Act states that the ownership of a copyright may be transferred in whole or in part by any means of conveyance or by operation of law. Further, the following section 201(d)(2) specifies that this principle of divisibility applied to each of the exclusive rights – print, adaptation, distribution, reproduction and performance – which could be divided, transferred and owned separately.

Now, for the first time, an author could license only the performance rights. But more specifically, the author could license only a portion of his/her performance rights. So, you see, the idea of transferring fractional shares of a copyright, or one of the exclusive rights of a copyright, is actually built into the copyright act. This is something the DOJ ruling completely ignored in its analysis when it interpreted the Consent Decrees to require the PRO’s to offer 100% licensing of their catalog.

The DOJ, however, was focused primarily on the user of the music, completely ignoring the creators. For the user, the DOJ felt it was egregious to have to go to all three PRO’s to get a license to perform one work. To be fair, the PRO’s have tiptoed gingerly around this issue for years. A license from one songwriter/publisher to perform a work should, in theory, be sufficient. That is, after all, the meaning of a non-exclusive license. The industry has avoided the user aspect of partial rights grants for years, requiring each user to obtain a “blanket license” from all three PRO’s in order to perform each PRO’s catalog (and consequently, glossing over the fact that a license to perform one individual work from the owner of copyright would suffice to perform the work). In this way, each PRO could distribute the royalties collected on the benefit of their members to each one respectively according to their own algorithms.

That process may change if the DOJ’s consent decree remains in effect. Each PRO would have to agree who collects for a particular license, and then credit the other with their share. This would require each one to adjust their rates accordingly and account to and pay some of the royalties received to the other PRO’s. While it can’t be stated definitively, one just feels that this process will somehow negatively impact the songwriters and publishers, and not the PRO’s or the venues.

Most people in the industry predict that application of this “full-work” licensing approach will throw the music industry in complete and utter chaos – and they’re probably correct. But, as I said earlier, all hope is not yet lost. First, the DOJ gave ASCAP and BMI one year to get their act together and start operating on the 100% licensing principle they outlined. Second, for perhaps the first time in history, ASCAP and BMI are bedfellows (you know what they say of politics) in that they have agreed to a course of reaction: BMI is appealing the DOJ’s ruling while ASCAP is lobbying Congress for relief. ASCAP and BMI both announced that they would join forces to fight this common foe.

The president of BMI, Michael O’Neill, was quoted in the Tennessean in response:

The DOJ’s interpretation of our consent decree serves no one, not the marketplace, the music publishers, the music users, and most importantly, not our songwriters and composers who now have the government weighing in on their creative and financial decisions. Unlike the DOJ, we believe that our consent decree permits fractional licensing, a practice that encourages competition in our industry and fosters creativity and collaboration among music creators, a factor the DOJ completely dismissed.

For her part, CEO of ASCAP, Elizabeth Matthews stated that:

The DOJ decision puts the U.S. completely out of step with the entire global music marketplace, denies American music creators their rights, and potentially disrupts the flow of music without any benefit to the public. That is why ASCAP will work with our allies in Congress, BMI and leaders within the music industry to explore legislative solutions to challenge the DOJ’s 100 percent licensing decision and enact the modifications that will protect songwriters, composers and the music we all love.

Most people outside the industry will have no idea how significant it is that both of this PRO’s are cooperating with each other on this issue. ASCAP’s and BMI’s joint efforts may serve to put pressure on Congress to address an aging Copyright Act and implement some of the recommendations made by the Copyright Office in 2015, namely, the creation of a mega “Music Rights Organization” or MRO that, among other things, licenses all exclusive rights of the copyright owner, including both performance and mechanical rights. The Copyright Office also recommended an elimination of the Consent Decrees. U.S. Rep. Bob Goodlatte, R-Virginia, who is chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, is expected to recommend changes to the Copyright Act that could be taken up on the 2017 Congress.

In the midst of all of this activity, SESAC is again quietly biding their time, acquiring Harry Fox (mechanical rights) and Rumblefish (a “record label” including digital performance rights) in preparation for becoming perhaps the first effective “MRO.”

No one truly knows the ultimate outcome of all of this but one thing is certain: the history of performance rights organizations in America continues to evolve. The copyright law is very complex and have evolved over the years since its passage in 1976. That law took almost half a century to pass and there is no reason to believe that a new revision wouldn’t take just as long given the multiple competing and often conflicting interests of various stakeholders. But patience is not the songwriter’s only recourse here: write your elected representative in Washington and plead your case, as free speech is the only right that will make a difference in this fight.

[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

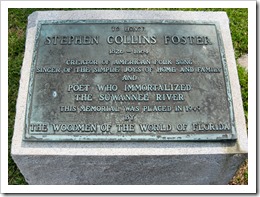

ons. In the mid 1800’s, when Stephen Foster wrote The Suwannee River, Oh! Susanna, Camptown Races, Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair, and Old Kentucky Home, the 1790 Copyright Act only protected “maps, charts and books” and thus did not extend to musical compositions. The only way Foster could conceive of earning an income from his craft was to sell his sheet music to traveling troubadours and minstrel shows, such as “Christy’s,” that traveled the country. The strategy worked in terms of getting his music exposure, but without adequate protective remedies, it created an environment where unscrupulous and dishonest publishers “bootlegged” his work and sold copies for their own profit. While most of the country knew Foster’s work (even today) because of this exploitation, he died a pauper in 1864 with less than a dollar to his name. So much for the post-Napster argument that illegally downloading and streaming music actually makes money for its creator by giving it wider exposure!

ons. In the mid 1800’s, when Stephen Foster wrote The Suwannee River, Oh! Susanna, Camptown Races, Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair, and Old Kentucky Home, the 1790 Copyright Act only protected “maps, charts and books” and thus did not extend to musical compositions. The only way Foster could conceive of earning an income from his craft was to sell his sheet music to traveling troubadours and minstrel shows, such as “Christy’s,” that traveled the country. The strategy worked in terms of getting his music exposure, but without adequate protective remedies, it created an environment where unscrupulous and dishonest publishers “bootlegged” his work and sold copies for their own profit. While most of the country knew Foster’s work (even today) because of this exploitation, he died a pauper in 1864 with less than a dollar to his name. So much for the post-Napster argument that illegally downloading and streaming music actually makes money for its creator by giving it wider exposure! ewfangled and emerging technologies, and at least in partial deference to Stephen Foster’s unfortunate demise, Congress finally passed the 1909 Copyright Act which provided copyright protection for musical compositions, giving them an initial term of 28 years with one 28-year renewal period for the purpose of “prevent[ing] the formation of oppressive monopolies” which might limit those rights. See, H.R. Rep. No. 2222, 60th Cong., 2nd Sess., p. 7. Now, these newly protected musical compositions could be performed and embodied in sound recordings (although sound recordings were still not protected by federal law at this time), which could themselves be performed in broadcasts over the radio waves. It was an exciting time in the music business, which saw the rise of music publishers, record labels, radio stations, Harry Fox and all three performance rights organizations, ASCAP, SESAC and BMI, in that order.

ewfangled and emerging technologies, and at least in partial deference to Stephen Foster’s unfortunate demise, Congress finally passed the 1909 Copyright Act which provided copyright protection for musical compositions, giving them an initial term of 28 years with one 28-year renewal period for the purpose of “prevent[ing] the formation of oppressive monopolies” which might limit those rights. See, H.R. Rep. No. 2222, 60th Cong., 2nd Sess., p. 7. Now, these newly protected musical compositions could be performed and embodied in sound recordings (although sound recordings were still not protected by federal law at this time), which could themselves be performed in broadcasts over the radio waves. It was an exciting time in the music business, which saw the rise of music publishers, record labels, radio stations, Harry Fox and all three performance rights organizations, ASCAP, SESAC and BMI, in that order.

BMI and ASCAP have been adversaries ever since. ASCAP, of course, had the upper hand, since they were first to market and arose out of the Tin Pan Alley environment. ASCAP did not take kindly to being shut out of the lucrative broadcast market and the two organizations began a decades long fight for the music users. This conflict ultimately caught the attention of the DOJ, who sued each entity under the Sherman Act (anti-trust) to address their comparative market power and balance the weight of power. The result of the DOJ’s involvement were the consent decrees that, to this day, govern how terrestrial radio (Either AM/FM) digital rebroadcasts, and/or venues such as bars and arenas, license the performance of compositions.

BMI and ASCAP have been adversaries ever since. ASCAP, of course, had the upper hand, since they were first to market and arose out of the Tin Pan Alley environment. ASCAP did not take kindly to being shut out of the lucrative broadcast market and the two organizations began a decades long fight for the music users. This conflict ultimately caught the attention of the DOJ, who sued each entity under the Sherman Act (anti-trust) to address their comparative market power and balance the weight of power. The result of the DOJ’s involvement were the consent decrees that, to this day, govern how terrestrial radio (Either AM/FM) digital rebroadcasts, and/or venues such as bars and arenas, license the performance of compositions.

edroom in Oklahoma. He sent a few tracks to Steven Battey in LA. The Battey brothers had platinum success with the likes of Justin Bieber, David Guetta, Madonna, and Flo Rida, just to name a few. At that time, Jackie Boyz had just acquired new management under Iain Pirie (Co-Producer of American Idol, 19th Entertainment, Carrie Underwood). Steven Battey was planning on moving to Nashville to develop his own writing in country music. He liked what Sammy sent him, so the two met in Nashville and hit it off. They immediately started writing/producing tracks together and doing co-writes with various songwriters in Nashville. Before long, Sammy found himself writing with the brotherly team, including Carlos, and the three formed a unique bond. Sammy’s deal with the Jackie Boyz/Razor & Tie venture came as a result of the momentum that built from his experience with Steven & Carlos Battey, with whom he formed a tight knit writing and production team.

edroom in Oklahoma. He sent a few tracks to Steven Battey in LA. The Battey brothers had platinum success with the likes of Justin Bieber, David Guetta, Madonna, and Flo Rida, just to name a few. At that time, Jackie Boyz had just acquired new management under Iain Pirie (Co-Producer of American Idol, 19th Entertainment, Carrie Underwood). Steven Battey was planning on moving to Nashville to develop his own writing in country music. He liked what Sammy sent him, so the two met in Nashville and hit it off. They immediately started writing/producing tracks together and doing co-writes with various songwriters in Nashville. Before long, Sammy found himself writing with the brotherly team, including Carlos, and the three formed a unique bond. Sammy’s deal with the Jackie Boyz/Razor & Tie venture came as a result of the momentum that built from his experience with Steven & Carlos Battey, with whom he formed a tight knit writing and production team.

ican support and control, there is much more optimism. The Bill, introduced by Congressman Doug Collins (R-Ga), seeks to amend Section 114 and 115 of the Copyright Act to implement some of the suggestions proposed by the Copyright Office’s report. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), a senior senator and member of the critical Judiciary Committee, co-sponsored the legislation and has frequently been an advocate for songwriters. For one thing, it would allow the royalty courts to adapt the “fair market rate” standards when setting mechanical license rates under Section 115, and allow them to consider royalties paid to recording artist when setting rates for songwriters under Section 114. Most people believe that this would be a more profitable structure for songwriters and music publishers.

ican support and control, there is much more optimism. The Bill, introduced by Congressman Doug Collins (R-Ga), seeks to amend Section 114 and 115 of the Copyright Act to implement some of the suggestions proposed by the Copyright Office’s report. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), a senior senator and member of the critical Judiciary Committee, co-sponsored the legislation and has frequently been an advocate for songwriters. For one thing, it would allow the royalty courts to adapt the “fair market rate” standards when setting mechanical license rates under Section 115, and allow them to consider royalties paid to recording artist when setting rates for songwriters under Section 114. Most people believe that this would be a more profitable structure for songwriters and music publishers.

The passage of the Digital Economy Act in England last year has resulted in a surge of articles that claim that the negative impact of illegal downloading of MP3’s on the record industry has been “debunked” and that, in fact, studies confirm the opposite, that there is no significant impact. I recently addressed one such claim on my blog in the article entitled

The passage of the Digital Economy Act in England last year has resulted in a surge of articles that claim that the negative impact of illegal downloading of MP3’s on the record industry has been “debunked” and that, in fact, studies confirm the opposite, that there is no significant impact. I recently addressed one such claim on my blog in the article entitled